As the world goes on, an exciting time is dawning for climate scientists. For years, they have wanted more certainty about the warming and cooling mechanisms in the atmosphere due to the influence of different types of clouds and aerosols. After years of preparatory work, a new cloud satellite is going to rigorously bring more certainty to humanity about this.

Lees dit artikel in het Nederlands onder de Engelse tekst

“This is happening with one of the most complex Earth observation missions in space ever: the European-Japanese Earth observation satellite EarthCARE,” say KNMI scientists Dave Donovan and Gerd Jan van Zadelhoff, who have been working on it for years, in leading scientific roles.

The Earth Clouds and Aerosol Radiation Explorer satellite, or EarthCARE for short, of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), will be launched Tuesday. Exciting for the scientists from De Bilt, for their many international colleagues, and historical for humankind in general.

Leap in atmospheric knowledge

Just what puzzle for humanity will EarthCARE solve? “Clouds come in all shapes and sizes,” the Dutch scientists explain. A dense white cloud reflects sunlight away from Earth, while thinner clouds can let some sunlight through, and clouds also trap thermal (heat) radiation from escaping to space. The balance between these processes determines if a cloud will cause warming or cooling.

That’s complex as it is, but aerosols further complicate the interplay. Aerosols are fine particles and droplets from nature (windblown desert sand, sea foam, volcanic ash) or from man (combustion soot). Aerosols also influence incoming and outgoing radiation, as well as the formation and properties of clouds. But how exactly? Atmospheric scientists worldwide are working together on models to describe and explain this. With measurements from the instruments on the EarthCARE satellite, these models will rapidly improve, and with them, our knowledge of how the atmosphere works and what to expect.

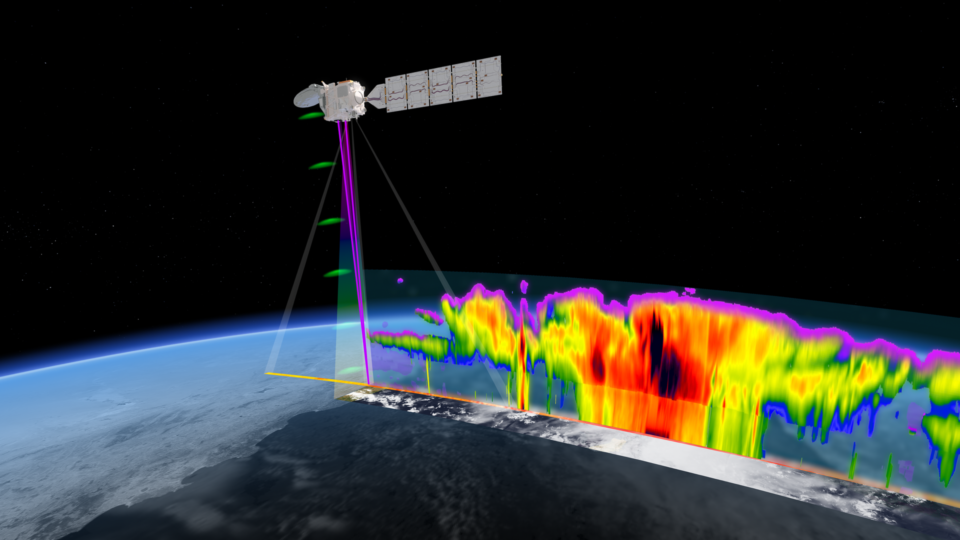

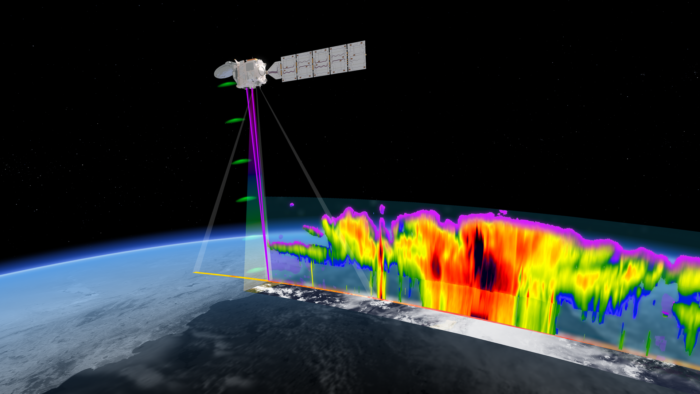

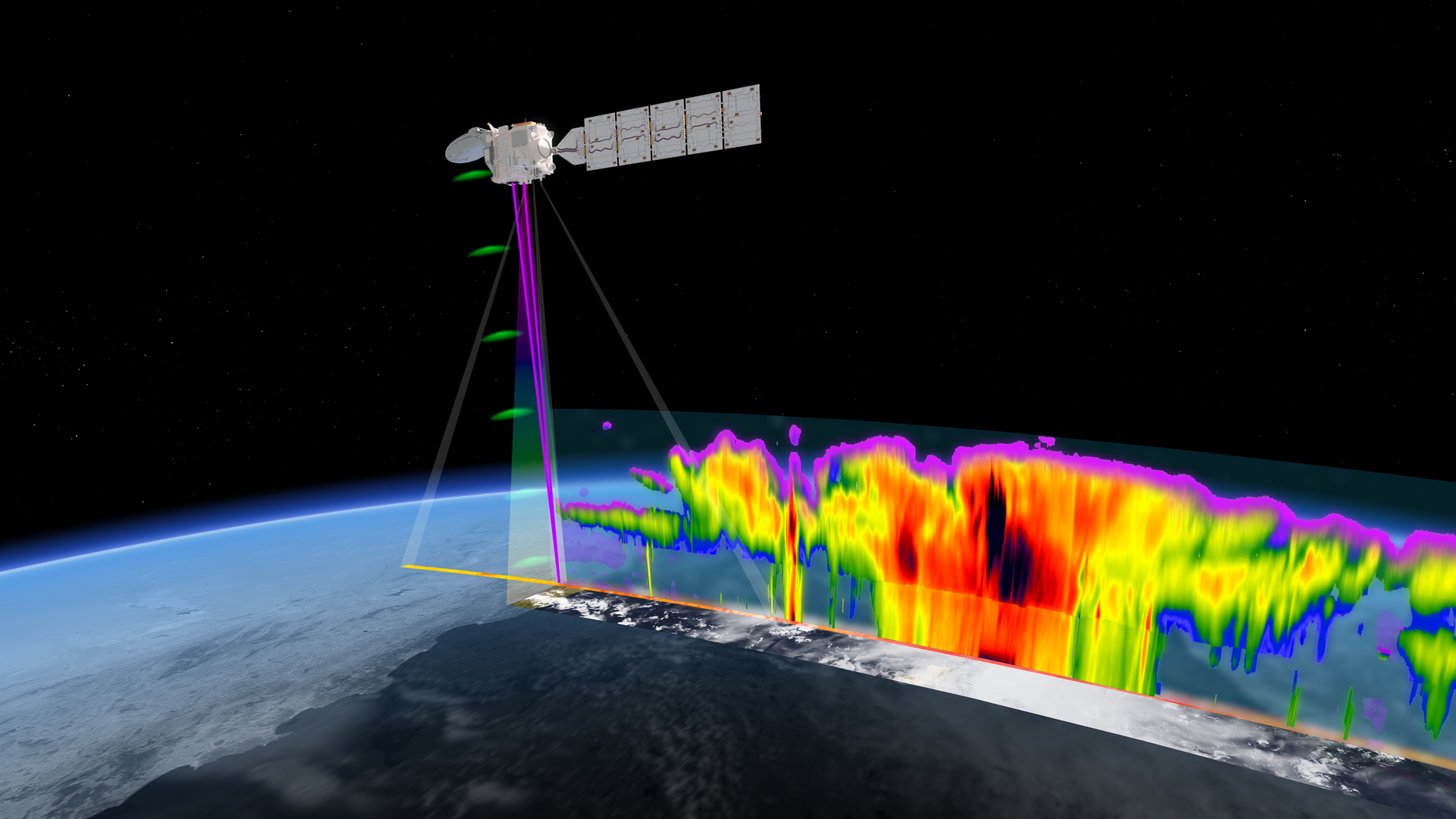

A 3D atmospheric image

Donovan and Van Zadelhoff explain how EarthCARE will provide this. “The satellite carries four instruments that together for the first time can build a complete and three-dimensional picture of what is happening in terms of cloud properties , the presence of aerosols and incoming and outgoing radiation,” they explain.

From theory to knowledge

Such a combined measurement was never available before EarthCARE. “This is a mission that can unify the important existing ideas about the workings of different mechanisms in the atmosphere and link them to each other, as well as to true measurements,” the scientists tell us. “This is a so-called ‘closure’ mission.

The Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) is leading the scientific teams for all four instruments, which will also help improve weather forecasting models.

What are the instruments capable of?

The Atmospheric Lidar (ATLID) transmits ultra-violet laser beam towards the Earth’s surface, and, thanks to its advanced design, is able to distinguish between light scattered by aerosol or clouds and light that has been scattered by the molecules that make up the atmosphere itself. This helps to accurately figure out how much light aerosols and clouds are reflecting and helps to identify cloud types like ice or liquid water, and aerosol types like desert dust or pollution.

The Cloud Profiling Radar (CPR) allows scientists to discern the vertical motion of rain, snow, ice and cloud droplets as they move at different speeds. The CPR observes their doppler effect for this purpose, something that could not be done from space before CPR.

The Multi-Spectral Imager (MSI) continuously measures horizontal images of ‘ordinary’ visible light and infrared light at different wavelengths, or colors. This also allows scientists to place the unique combination of vertical aerosol and cloud measurements from ATLID and the CPR into the broader “bird’s-eye view” of the atmosphere.

The Broad-Band Radiometer (BBR) continuously measures the total reflectance of solar radiation by the upper part of the atmosphere and the amount of emitted thermal energy escaping to space.

Scientists can compare all these measurements with their “radiative transfer models” in which scientists describe how ordinary clear air, aerosols, different cloud states and precipitation continually transition into one another, while reflecting sunlight back, letting it through, or keeping it “inside the greenhouse”.

“Are our assumptions about this correct? Do aspects still remain unclear? That’s what we’re going to systematically explore with EarthCARE,” Donovan and Van Zadelhoff tell us. “Not only does this apply to the radiation balance, but also to the weather”.

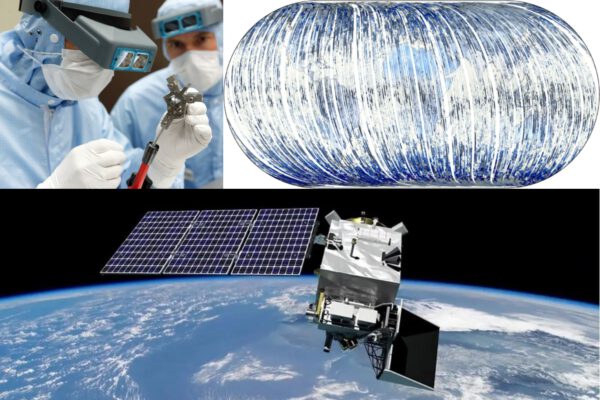

Building the impossible

Solving the gap in “radiative transfer” knowledge, has become a demanding life’s work for Dave Donovan. Donovan is a global expert on atmospheric measurements with lasers (LIDAR). He continued to advocate for the mission whose development was plagued by numerous technical challenges.

LIDARs require very high power, which is very unfavorable in a space instrument. “Making ATLID has been extra difficult,” he says. “High in the atmosphere, the air is thin, almost vacuum, but the materials the satellite is made out of release gases themselves. These compounds, combined with bright light radiation, can lead to chemical damage to occur on the optical surfaces themselves. This does not occur when operating similar equipment on Earth since Oxygen acts to clear the damaging compounds away. For ATLID, this problem was more difficult than for other LIDARS, because of the specific wavelength of light used.”

Also, the Doppler radar was a challenge. “And, according to critics, almost impossible,” Donovan says. “It requires a large antenna, and many high-voltage power units that need to be properly electrically isolated. Everything has to be packed together in a small space where components shouldn’t affect each other. But this proved to be a challenge”.

Meanwhile, every ounce of weight mattered to the lifetime of the satellite. “EarthCARE cannot fly too high in order to properly receive the reflected signals from the Lidar and Radar. But the lower the orbit, the shorter the lifetime, because of atmospheric drag. Low Earth orbits are not quite free of atmospheric molecules and this “wind resistance” will, over time, cause the satellite to slow down and descend toward the Earth.”

The list of design obstacles and technical obstacles, besides these examples, was extensive, says Donovan.

Coding the impossible

“At least as challenging as the technical obstacles, was designing the data processing,” the scientists tell us. Any scientific space instrument requires a well-designed data processing system with extensively tested algorithms. These must continuously translate large streams of zeros and ones into data about what the instrument actually observed in flight.

“The making of these so-called ‘retrieval algorithms’, in addition to the computer code writing itself, consists to a large extent of detecting and solving ‘bugs’, errors in the code, which make the results illogical and don’t seem to add up,” says Gerd-Jan van Zadelhoff. He is coordinating an international team of algorithm developers for EarthCARE.

“In this work, it helps a lot if there have been precursors that you can build on. Because if there are already real measurements, previous algorithms have been compared to them and fine-tuned.” But EarthCARE, with ATLID and the CPR, is bringing completely new measurement capabilities into space for which no suitable algorithms yet existed. “So writing the algorithms had to be done from scratch. For four instruments, measuring different things to reveal something together, this was an absolutely gigantic work,” the scientists tell us. Painstaking at a high scientific level.

17 algorithms, 30 data products

“As many as 17 of these so-called data retrieval algorithms were written for EarthCARE’s four instruments,” Van Zadelhoff says. “A handful translate the data stream from just one instrument, which then seems somewhat manageable. But most of the algorithms process measurements from two, three or even all four instruments.”

As zeros and ones from instruments are translated by the algorithms, dataproducts emerge. “For EarthCARE, there are as many as 30 dataproducts” he says.

Dataproducts are the reliable databases that scientists can use to conduct their research on aerosols, cloud formation, absorption and reflection of radiation, weather and all their interrelationships.

For example, one scientist will want to study the atmosphere after a volcanic eruption, and another will want to find out which types of aerosols are most efficient for heling clouds to form.

Data we’ve been awaiting for years

For all kinds of processes in the atmosphere, scientists around the world have been modeling pieces of the puzzle for the past decades. After years of waiting, EarthCARE is going to provide them with reliable and detailed datasets that show not only the “flat picture from above,” but also very detailed properties in the different vertical layers.

“The scientific community has been looking forward to the results for a long time”, the scientists say. “Now it’s really going to happen.”

For Further Information:

- ESA – EarthCARE: ESA’s cloud and aerosol mission

- TNO – Designed and developed the Multi Spectral Imager, see EarthCARE project page

- SRON and KNMI – Study the synergy between EarthCARE and SPEXone on PACE in project AIRSENSE

- KNMI – Door satelliet EarthCARE meer begrip van klimaatverandering

The Netherlands: a major atmospheric science country

The Netherlands is globally one of the bigger knowledge players when it comes to atmospheric science in many ways.

This goes for writing and refining models that describe air and climate,

it goes for designing and engineering space instruments with all their advanced optical, super-cold, fine-mechanical, flight-worthy technology. And it applies to the flawless design of instrument data processes.

The atmospheric knowledge landscape in the Netherlands is high-end but at the same time it has short lines of communication. Groups collaborate and find each other. KNMI is one of the partners within the Dutch ClearAir Consortium. Within this consortium, Dutch knowledge partners often play a leading role in answering the world’s most pressing atmospheric and climate questions.

Langverwachte wolkensatelliet gaat ontbrekende schakels in atmosfeer ontrafelen

Terwijl de wereld doordraait, breekt een opwindende tijd aan voor klimaatwetenschappers. Zij willen al jaren meer zekerheid over de opwarmende en afkoelende mechanismes in de atmosfeer door de invloed van verschillende soorten wolken en aerosolen. Na jaren van voorbereidend werk gaat een nieuwe wolkensatelliet de mensheid daarover rigoureus meer zekerheid brengen.

“Dat gebeurt met één van de meest complexe aardobservatiemissies in de ruimte ooit: de Europees-Japanse aardobservatiesatelliet EarthCARE”, vertellen de KNMI-wetenschappers Dave Donovan en Gerd Jan van Zadelhoff die er jaren aan hebben gewerkt, in een leidende wetenschappelijke rol.

De Earth Clouds and Aerosol Radiation Explorer satelliet (EarthCARE) van de European Space Agency (ESA) en de Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), wordt dinsdag gelanceerd. Spannend voor de wetenschappers uit De Bilt, hun vele internationale collega’s, en historisch voor de mensheid in het algemeen.

Sprong in atmosfeerkennis

Welke puzzel voor de mensheid wordt nou met EarthCARE precies opgelost? “Wolken komen in allerlei soorten en maten”, leggen de Nederlandse wetenschappers uit. Een dichte witte wolk houdt zonlicht juist bij de aarde weg, terwijl dunnere wolken een deel van zonlicht kunnen doorlaten, en wolken houden ook thermische (warmte) straling tegen die anders de ruimte in zou ontsnappen. De balans tussen deze processen bepaalt of een wolk opwarming of afkoeling veroorzaakt.

Dat is al complex genoeg, maar aerosolen maken het samenspel nog ingewikkelder. Aerosolen zijn fijne deeltjes en druppeltjes, uit de natuur (opwaaiend woestijnzand, zeeschuim, vulkaanas) of van de mens (verbrandingsroet). Die beïnvloeden ook in- en uitgaande straling, maar óók het ontstaan en de eigenschappen van wolken. Maar hoe precies? Atmosfeerwetenschappers wereldwijd werken samen aan de modellen om dit te beschrijven en verklaren. Met échte metingen van de instrumenten op de EarthCARE satelliet, zullen deze modellen snel verbeteren, en daarmee dus ook onze kennis over hoe het werkt en wat we kunnen verwachten.

Een 3D atmosfeerbeeld

Donovan en Van Zadelhoff leggen uit hoe EarthCARE daarvoor gaat zorgen. “De satelliet draagt vier instrumenten die sámen voor het eerst een compleet en driedimensionaal beeld kunnen opbouwen van wat er gebeurt net betrekking tot wolkeneigenschappen, aanwezigheid van aerosolen én in- en uitgaande straling”, vertellen ze.

Theorie wordt kennis

Zo’n gecombineerde meting was vóór EarthCARE nooit mogelijk. “Dit is een missie die de belangrijke bestaande ideeën over de werking van verschillende mechanismes in de atmosfeer kan verenigen en kan linken aan elkaar, én aan directe metingen”, vertellen de wetenschappers. “Een zogenoemde ‘closure’-missie.”

Het Koninklijk Nederlands Meteorologisch Instituut (KNMI) leidt de wetenschappelijke teams voor alle vier de instrumenten, die ook de weersvoorspellende modellen zullen helpen verbeteren.

Wat kunnen de instrumenten?

De Atmosferische Lidar (ATLID) stuurt een ultraviolet laserstraal loodrecht naar het aardoppervlak en, dankzij het geavanceerde ontwerp, is deze in staat om onderscheid te maken tussen licht dat verstrooid wordt door aerosolen of wolken en licht dat verstrooid wordt in de kolom door de moleculen waaruit de atmosfeer zelf bestaat. Dit helpt om nauwkeurig te bepalen hoeveel licht aerosolen en wolken weerkaatsen en helpt bij het identificeren van wolkentypen (bijv. ijs of vloeibaar water) en aerosolen (bijv. woestijnstof of vervuiling).

Met de Cloud Profiling Radar (CPR) kunnen wetenschappers – in diezelfde kolom – de verticale beweging van regen, sneeuw, ijs en wolkdruppels onderscheiden, omdat die met verschillende snelheden bewegen. CPR neemt daarvoor hun doppler-effect waar, iets wat met de CPR voor het eerst vanuit de ruimte van bovenaf kan.

De Multi-Spectral Imager (MSI) meet continu horizontale beelden van ‘gewoon’ licht en vele schakeringen van infraroodlicht. Zo kunnen wetenschappers de unieke combinatie van de verticale aerosol- en wolkmetingen ook plaatsen in het bredere ‘vogelperspectief’ van de atmosfeer.

De Broad-Band Radiometer (BBR) meet steeds de totale terugkaatsing van zonnestraling door het bovenste stuk van de atmosfeer en de hoeveelheid uitgezonden thermische energie die naar de ruimte ontsnapt.

De metingen kunnen wetenschappers vergelijken met hun ‘radiative transfer models’ waarin wetenschappers beschrijven hoe gewone heldere lucht, aerosolen, verschillende wolktoestanden en neerslag continu in elkaar overgaan, en daarbij ook zonlicht terugkaatsen, doorlaten, of ‘binnen de broeikas’ houden.

“Kloppen onze veronderstellingen daarover? Blijft er nog steeds een aspect onduidelijk? Dat gaan we met EarthCARE systematisch uitvinden”, vertellen Donovan en Van Zadelhoff. “En dat geldt niet alleen voor de stralingsbalans, maar ook voor het weer. Soms zijn ergens opvallend veel hoge cirruswolken. Weten we straks waarom?”

Technische uitdagingen

Het oplossen van het gat in de ‘radiative transfer’ kennis, is een veeleisend levenswerk geworden van Dave Donovan. Donovan is een wereldwijde expert op het gebied van atmosfeermetingen met lasers (LIDAR). Hij bleef zich sterk maken voor de missie die ervaren ruimtemissiebouwers technisch gezien voor onmogelijk hielden, vanwege schijnbaar onneembare hobbels.

LIDARs hebben erg veel vermogen nodig, wat in een ruimte-instrument erg ongunstig is. “ATLID maken was extra moeilijk”, zegt hij. “Hoog in de atmosfeer is de lucht ijl, bijna vacuüm, zodat de materialen sneller gassen loslaten. In combinatie met felle lichtstraling kunnen chemische beschadigingen op de lichtmeters zelf ontstaan. Zuurstof, dat de meters een beetje schoon houdt, ontbreekt daar. Voor ATLID was dit probleem lastiger dan bij andere LIDARS, vanwege het specifieke licht dat we meten.”

Ook de doppler-radar was een uitdaging. “En volgens critici bijna onmogelijk”, vertelt Donovan. “Die vraagt een grote antenne, en veel powerunits met een hoog voltage die je goed moet isoleren. En alles moet samengepakt in een kleine ruimte waar componenten elkaar niet mogen beïnvloeden.”

Intussen telde ook elke gram gewicht voor de levensduur van de satelliet. “Want EarthCARE kan voor een goede ontvangst van het terugkaatsende signaal niet té hoog vliegen. Maar hoe lager de baan, hoe korter de levensduur, omdat de satelliet sneller naar de aarde afzakt, tot het punt waarop de aarde de satelliet naar zich toe trekt.” Donovan kan de lijst technische obstakels nog veel uitputtender maken.

Dataproces uitdagingen

“Minstens zo uitdagend als de technische obstakels, was het ontwerpen van de dataverwerking”, vertellen de wetenschappers. Elk wetenschappelijk ruimtemeetinstrument vereist een goed ontworpen dataproces met uitvoerig geteste algoritmen. Die moeten continu grote stromen nullen en enen vertalen naar data, over wat het instrument nou eigenlijk heeft waargenomen tijdens de vlucht.

“Het schrijven van deze zogenaamde ‘retrieval algoritmes’ bestaat naast het schrijven zelf voor een flink deel uit het opsporen en oplossen van ‘bugs’, foutjes in de code, waardoor de resultaten onlogisch zijn en niet lijken te kloppen”, vertelt Gerd-Jan van Zadelhoff. Hij coördineert voor EarthCARE een internationaal team van algoritme ontwikkelaars.

Geen voorgangers

“In dit werk helpt het erg als er voorlopers zijn geweest waarop je kunt voortbouwen. Want als er al echte metingen zijn, zijn eerdere algoritmes daarmee vergeleken en bijgeschaafd.” Maar EarthCARE brengt met ATLID en met CPR compleet nieuwe meetmogelijkheden in de ruimte waar nog geen blaadje code voor bestond. “Dus moest het schrijven van de algoritmen ook van meet af aan beginnen. Voor niet een, maar vier instrumenten, die verschillende dingen meten om sámen iets te onthullen, was dit helemaal een gigantische klus”, vertellen de wetenschappers. Monnikenwerk dus, maar dan ook nog eens op hoog wetenschappelijk niveau.

17 algoritmes, 30 dataproducten

“Voor de vier instrumenten van EartCARE zijn er wel 17 van die zogenaamde data retrieval algoritmes geschreven”, vertelt Van Zadelhoff. “Een handvol vertaalt de gegevensstroom van één instrument, wat dan nog enigszins overzichtelijk lijkt. Maar de meeste verwerken de metingen van twee, drie of zelfs álle vier de instrumenten.”

Als nullen en enen uit instrumenten door de algoritmes worden vertaald, komen daar dataproducten uit. “Voor EarthCARE zijn dat er maar liefst 30.”

Dataproducten zijn de betrouwbare gegevensbibliotheken waar wetenschappers uit kunnen putten voor hun onderzoek naar aerosolen, wolkvorming, absorptie en weerkaatsing van straling, het weer en al hun onderlinge samenhang.

De ene wetenschapper zal bijvoorbeeld de atmosfeer na een vulkaanuitbarsting willen onderzoeken, en de ander wil uitzoeken welk type aerosol water aantrekt en een wolk begint te vormen, en welke juist water afstoot. “

Data waar we jarenlang naar uitkeken

Voor allerlei processen in de atmosfeer hebben wetenschappers wereldwijd de afgelopen decennia al stukjes model gemaakt. Na jaren wachten gaat EarthCARE hen de betrouwbare en gedetailleerde datasets leveren die niet alleen het ‘platte plaatje van bovenaf’ laten zien, maar ook heel gedetailleerd de dynamiek in de verschillende lagen.

“De wetenschappelijke wereld ziet al lange tijd uit naar de resultaten. Nu gaat het echt gebeuren.”

Nederland is atmosfeerkennisland

Nederland is wereldwijd een van de grotere kennisspelers als het gaat om atmosfeerwetenschap op vele fronten.

Dat geldt voor het schrijven en verfijnen van modellen die lucht en klimaat beschrijven,

dat geldt voor het ontwerpen en realiseren van ruimte-instrumenten met al hun geavanceerde optische, superkoude, fijnmechanische, vluchtwaardige technologie. En dat geldt voor het feilloos inrichten van de dataprocessen bij instrumenten.

Het atmosfeer-kennislandschap in Nederland is hoogwaardig, maar heeft tegelijk korte lijnen. KNMI is een van de partners binnen het Nederlandse ClearAir Consortium. Binnen dit consortium sturen Nederlandse kennispartners in een vaak leidende rol aan op het beantwoorden van de meest urgente atmosfeer- en klimaatvragen wereldwijd.